Have you ever landed on a website, encountered a cookie popup, but couldn’t spot a ‘reject’ button? You then attempt to adjust the cookie settings, only to be puzzled, so you click on ‘accept all’ and move on. We’ve all been there.

While this might look like a case of poor user experience, these are often deliberate design practices or “dark patterns” that prompt users to make decisions they might not have chosen otherwise. In recent years, there has been a growing consensus that online interfaces hold excessive power in influencing users’ decisions and that companies use them to trick consumers into choices that further their business interests.

What are dark patterns?

Harry Brignull, a web designer, introduced the term “dark patterns” in 2010 to refer to deceptive design in user interfaces that manipulate users into making certain choices or taking specific actions they would not take if they had a real choice or understood it. For example, pre-checked boxes that force users into subscribing to marketing emails when they sign up for a product or service.

Dark patterns often capitalize on cognitive biases and choice architecture to steer users into making decisions based on emotions rather than rationality. This can lead to user frustration, decreased trust, ethical concerns and non-compliance.

As dark patterns often violate the consumer’s right to informed and free consent, they are in breach of data protection laws that require explicit consent from consumers, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU and UK, and the California Protection Rights Act (CPRA) in the US etc.

How do dark patterns affect users?

In a 2019 study of 80,000 German users, it was found that even small UI design decisions (such as changing the position of the banner on-screen) can have a major impact on how people interact with the cookie consent banner.

In a 2020 study on the top 10,000 websites in the UK, researchers analysed three features: 1) whether the consent was given explicitly or implicitly 2) whether it was as easy to reject cookies as it is to accept and 3) if the banner contained pre-ticked boxes. The study found that less than 12% of websites were compliant with GDPR.

The constant appearance of cookie banners also leads to what many refer to as ‘consent fatigue’ where users just want to somehow dismiss the banner, leading to people agreeing to share way more personal data than they would like.

GDPR on dark patterns in consent

While the GDPR does not directly address dark patterns, it plays an important role in regulating deceptive design practices. As consent is an important legal basis for processing personal data under the GDPR, the law defines what constitutes valid consent.

The GDPR defines consent as:

“any freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes… by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.”

In 2022, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) published guidelines on dark patterns in social media platform interfaces and noted that dark patterns can hinder the users’ ability to provide “freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous consent”, as required to comply with the GDPR.

In 2023, the EDPB and the supervisory authorities (SA) from EEA member states, joined hands to form a ‘Cookie Banner Taskforce’ that investigated and published their findings on dark patterns in cookie banners.

EDPB Guidelines:

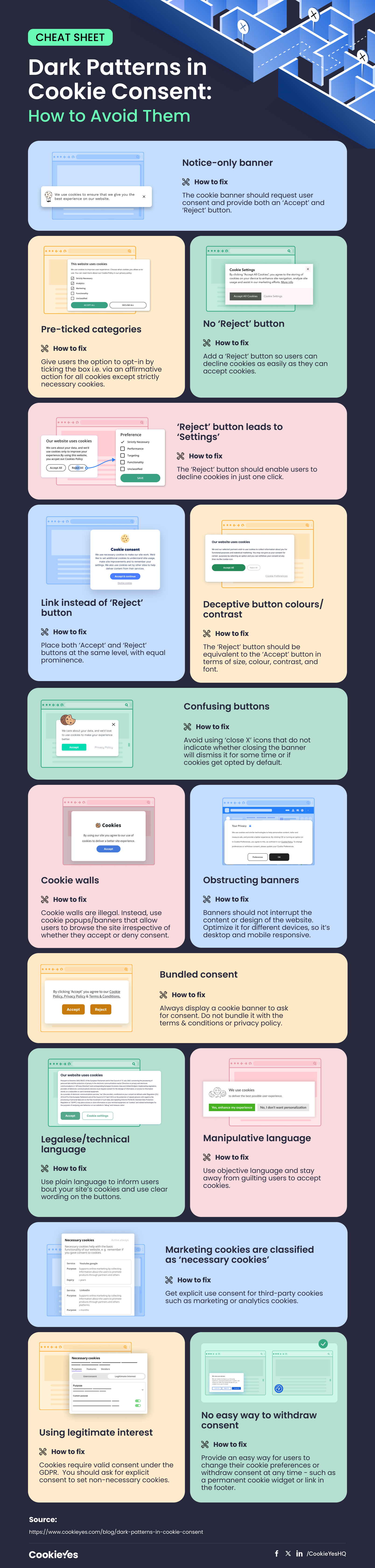

In the following section, we summarize examples of dark patterns, as noted in EDPB reports, and other studies and provide guidelines to avoid them while implementing a cookie banner on your site.

Dark patterns in cookie consent banners

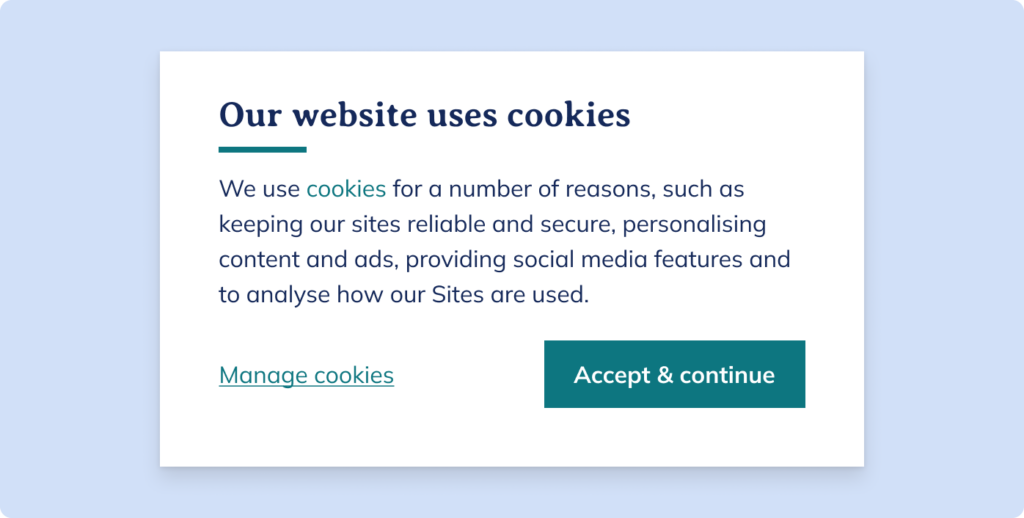

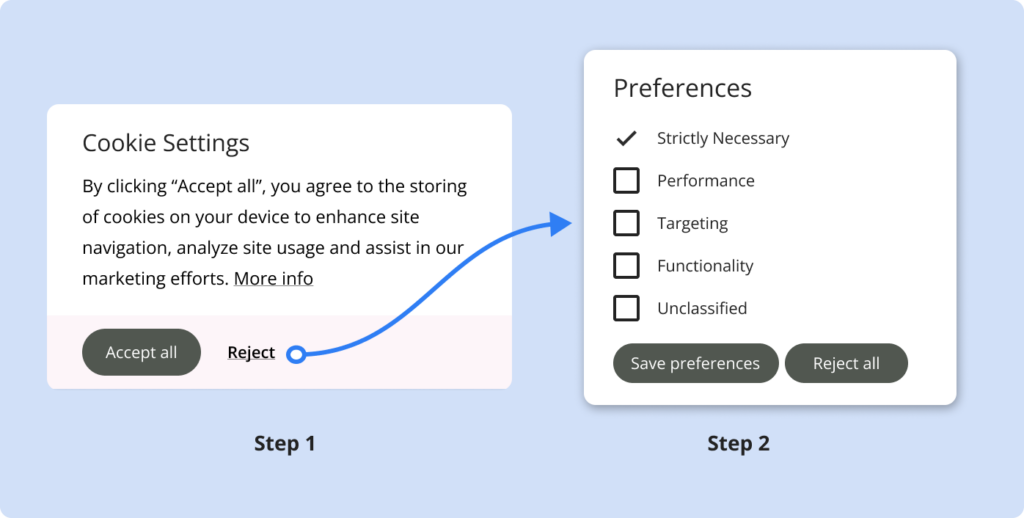

No reject button in the banner’s first layer

You often see banners that do not have a ‘Reject’ button in the first layer. Such banners do not give the users an easy choice to reject cookies, an infringement of their right to ‘freely given’ consent.

In 2022, French regulator, CNIL, fined Google €150 million and Facebook €60 million for making it difficult and confusing for users to reject cookies.

The first layer of the cookie banner should have a clear button that enables users to reject all cookies.

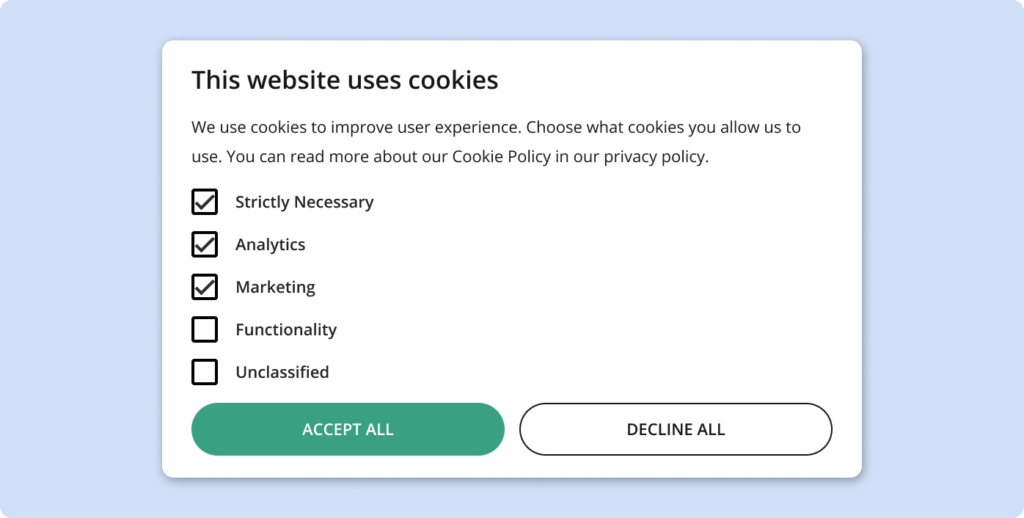

Pre-checked cookie categories

Sometimes, cookie banners have pre-ticked boxes on the banner’s second layer. This means even categories other than the strictly necessary cookies will be enabled by default. Making one option the standard or default, and requiring users to switch to another option actively is a dark pattern.

Recital 32 of GDPR states that “Silence, pre-ticked boxes or inactivity” do not constitute consent. To be GDPR compliant, consent should be specific and should involve affirmative action. Therefore pre-ticked boxes in cookie banners are not valid forms of consent.

Cookie banners should not include pre-ticked cookie categories. Only strictly necessary can be enabled by default.

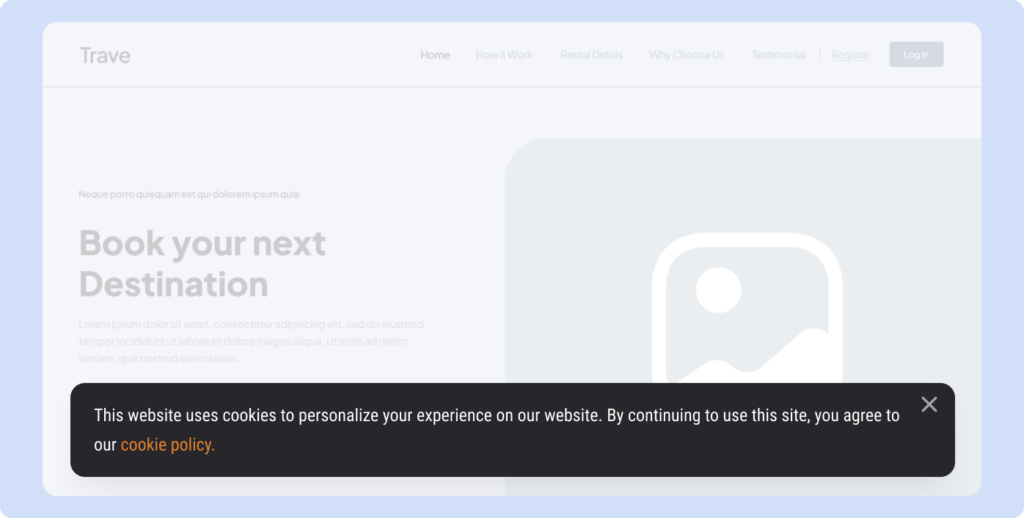

Notice-only banner

Certain cookie banners have no accept or reject button but only serve as a notice to visitors that cookies are used on the site. Such banners assume the user’s consent because they browse the website or navigate the webpage.

The assumption is that users accept the terms and conditions by continuing to use the website. However, GDPR requires consent to be a “clear affirmative action”; implied consent is not valid.

Cookie banners should provide clear options for users to accept and reject cookies to comply with GDPR.

Deceptive link design

Some cookie banners include a link, not a button, as an option to reject cookies. When links are used instead of buttons, there is no prominent visual cue to draw the user’s attention to this option.

Sometimes, this link takes you to a ‘Settings’ or ‘Preferences’ tab in the second layer where you can reject cookies. Here, the user has to take multiple actions to reject cookies i.e. there are more clicks involved in rejecting cookies.

Both cases do not constitute valid consent as the option to decline cookies should be upfront, not hidden in plain sight and it must be as easy to decline cookies as it is to accept them.

Provide a ‘Reject’ button in the first layer of your banner with equal prominence as the ‘Accept’ button and allow users to reject all cookies in one click.

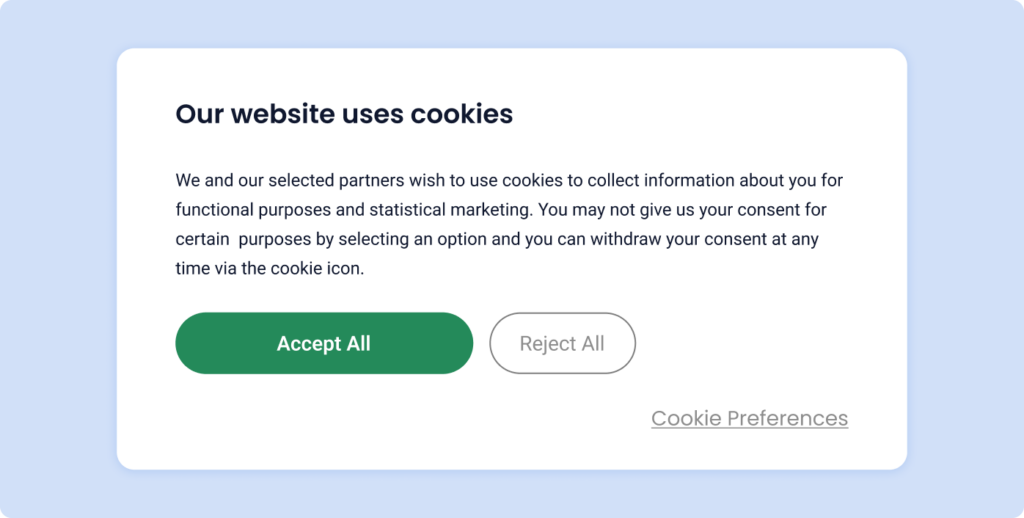

Deceptive button colours and contrast

We often see high and low contrasting colours used for buttons in cookie banners, where the “accept” button stands out or is highlighted. This includes using larger fonts and high contrast for accept buttons that draw users’ attention and minimise their attention to other available options.

Avoid using deceptive button colours or contrast for your buttons that nudge users into accepting cookies.

Using legitimate interest

Some websites use legitimate interest as their legal basis for dropping non-essential cookies such as analytics and advertising cookies, without collecting valid consent for their use. Legitimate interest can be used only when obtaining personal data is necessary, and there are no alternative methods to accomplish a specific legitimate goal.

Rely on explicit consent for setting non-necessary cookies such as advertising cookies. Using ‘legitimate interest’ for such cookies is not GDPR compliant.

Defining marketing cookies as necessary cookies

Have you ever noticed that sometimes websites drop marketing or analytics cookies from tools such as Google Analytics on your browser despite you rejecting cookies? This happens because GDPR exempts ‘strictly necessary’ cookies from the requirement of consent and website operators falsely classify advertising or analytics cookies as part of strictly necessary cookies and drop them without the user’s consent.

This is a non-compliant practice as such cookies cannot be considered as strictly necessary for a website to function, as per the definition in the ePrivacy Directive.

Do not classify marketing or analytics as strictly necessary. Refer to the EU’s Opinion on Cookie Consent Exemption to understand the two exemption criteria established under Article 5.3 ePrivacy Directive.

No easy way to withdraw consent

Sometimes there is no easily accessible option on the website to withdraw consent later on. As per GDPR, it must be as easy to withdraw consent as it is to give consent. In cases where users want to change their cookie preferences later on, they should be able to do so easily.

Provide an easy way for users to withdraw their consent, such as a permanently visible floating icon or a prominently located link on the footer to call back the cookie banner.

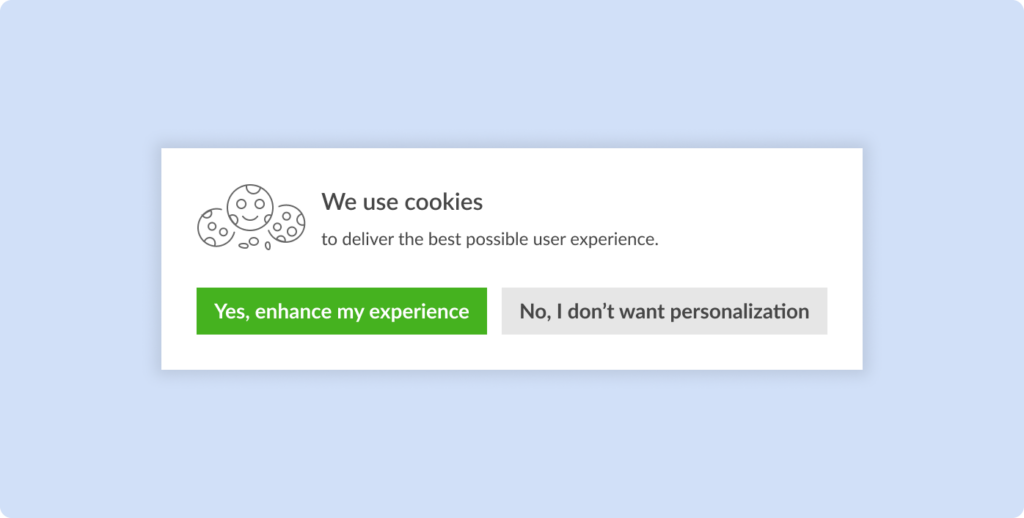

Manipulative language

Some banners use confusing language that makes users more susceptible to accepting cookies without realizing what they are agreeing to. This could be when text uses positive framing (e.g. “We use cookies to deliver the best possible user experience”) without mentioning the complete information about cookies such as their use in targeted advertising.

Some may use negative framing to imply that users will be missing out on functionalities if users they do not consent. (e.g. “If you decline cookies some nice features of the site may be unavailable”). As per GDPR’s transparency principle, you should provide the information in a “using clear and plain language”

Use clear, straightforward language and include information about (i) the cookies used (ii) their purposes and (iii) how to consent and/or reject these cookies.

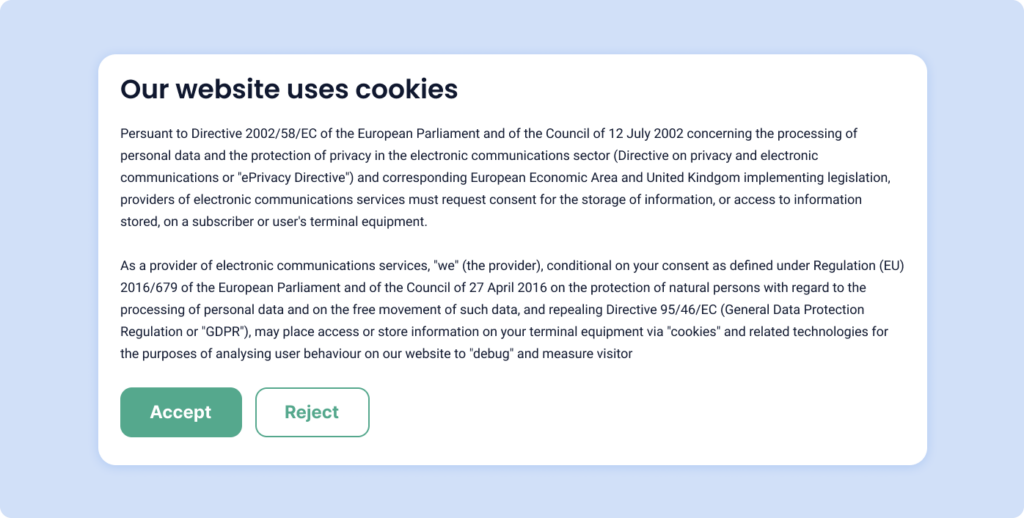

Complex language or legalese

Some cookie consent notices use complex legal language or jargon. This can hinder readability for an average user and makes the message less clear.

Use plain and simple language that will help users understand the information so that they can provide informed consent

Cookie walls

Cookie walls are examples of forced action where users are only allowed to access a website if they accept cookies. If refusing consent leads to a denial of the service, then it cannot be considered as freely given consent, as required under the GDPR.

EDPB consent guidelines state that “access to services and functionalities must not be made conditional on the consent of a user… (so-called cookie walls)”.

Do not use cookie walls that deny users access to the website unless consent is given. Access to your website should not be based on users’ consent to processing their data.

Cheat Sheet: How to avoid dark patterns

CPRA on dark patterns in consent

The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) addresses dark patterns and states that, “…agreement obtained through use of dark patterns does not constitute consent.”

As per CPRA, dark patterns are:

“a user interface designed or manipulated with the substantial effect of subverting or impairing user autonomy, decision-making, or choice, as further defined by regulation.”

The CPRA expressly states that “…agreement obtained through the use of dark patterns does not constitute consent”. The draft CPRA regulation provides a list of guidelines to avoid the use of dark patterns:

Easy to understand

Use language that is easy to understand – use plain, straightforward language and avoid technical or legal jargon.

Symmetry in choice

- Provide distinct options to “Accept” or “Decline” to opt into the sale or use of personal data instead of using options like “Yes” and “Ask me later” or “More Information.”

- Avoid displaying one choice prominently over the other such as a bigger or noticeable “Yes” button over a less conspicuous “No” button.

No confusing language or interactive elements

- Avoid interactive elements that are confusing such as the use of “on” or “off” toggles or buttons.

- Do not use double negatives, for instance, using “Yes” or “No” next to the statement “Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information”.

No manipulative language or choice architecture

- Avoid guilty or shaming language: For example, when offering a discount, you cannot use manipulative language such as “Yes” to accept and “No, I like paying full price” to decline.

- Avoid bundling reasonably expected purposes with other purposes. For example, if you offer a location-based service on your website/app, you can’t bundle your core offering with consent to the sale of the consumer’s geolocation data.

Easy to execute

- Do not add unnecessary burden or friction when users want to opt-out. For instance, when a user clicks on “Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information”, don’t make them search or scroll through a privacy policy or webpage to submit the opt-out request.

- Ensure that you don’t use circular or broken links for your opt-out requests.

Note: Similar to CPRA, other state-level data privacy regulations in the US such as the Colorado Privacy Act also address dark patterns and prohibit their use when obtaining consent.

CookieYes for compliant consent management

Implementing a functional cookie consent management platform is the best way to ensure compliance and avoid dark patterns on your website. CookieYes lets you deploy a compliant cookie consent banner to ensure that you only obtain valid consent and that nothing is tracked without user consent.

With CookieYes CMP, you don’t have to spend hours on consent management — use our compliant banner templates, customize your settings and go live in minutes!

- Google-certified CMP partner that supports Google Consent Mode V2

- Custom cookie consent banners that can be geo-targeted

- Supports 170+ languages with auto-translation in 41 languages

- IAB TCF v2.2 compliant cookie banner

- Centralized audit trail for proof of compliance

- Scheduled cookie scanning and auto-updating cookie list

- Free legal policy generators and more

Frequently Asked Questions

What are dark patterns in cookie consent?

Dark patterns in cookie consent are design practices that can manipulate and confuse users to make consent choices that are preferred by website owners and not users.

Dark patterns are often used by websites to trick users into giving consent for all cookies or misdirect them to give consent for analytics and marketing cookies that can track them.

What are dark patterns in GDPR?

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) does not define dark patterns explicitly. However, principles like fairness and transparency outlined in Article 5, and the conditions of consent outlined in Article 4 (11) and (7) form the basis for determining whether a design qualifies as a dark pattern.

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) launched guidelines on deceptive design patterns in social media interfaces and defines dark patterns as “interfaces and user experiences implemented…that lead users into making unintended, unwilling and potentially harmful decisions in regards to their personal data with the aim of influencing users’ behaviours”.

What is the legality of dark patterns?

The use of “dark patterns” has been controversial for a long time and regulators have been catching up. While the GDPR does not expressly ban dark patterns, GDPR’s principles on transparency and consent set the precedent to regulate dark patterns in the EU. With the passage of the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, EU lawmakers have taken explicit steps to counter dark patterns used by online platforms and core service providers.

In the US, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has adopted aggressive enforcement for dark patterns. State-level privacy laws, notably the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) and the Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) also have provisions to address dark patterns.

![Dark Patterns in Cookie Consent: How to Avoid Them [With Cheat Sheet]](https://www.cookieyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Dark-Patterns.png)